by Dom Nozzi

The following is a summary of a talk I was invited to give at a PLAN-Boulder County forum on Friday, January 24. As a town and transportation planner, I cautioned Boulder not to put too much emphasis on easing car traffic flows—particularly by such conventional methods as adding a second turn lane at intersections or requiring a developer to provide too much car parking. I described the ingredients of a healthy, vibrant city, summarized how a seemingly beneficial city objective of reducing traffic congestion can often undermine important Boulder objectives, and offered a number of strategies that would help Boulder both properly manage transportation and promote its long-range goals.

A great city is compact, human scaled, has a slow speed center, and promotes gatherings of citizens that catalyze “synergistic interaction” (brilliant ideas and innovations, as the sum becomes greater than its parts). Most importantly, a quality city does exceptionally well in promoting “exchanges” of goods, services, and ideas, which is the most important role of a city, and is best promoted by the interaction that occurs through compact community design.

About 100 years ago, automakers, home builders, and oil companies (“the Sprawl Lobby”) started realizing that they could make lots of money by creating what has since become a self-perpetuating vicious cycle in communities. If communities could be convinced to ease the flow of car traffic by building enormous highways and parking lots (and subsidizing car travel by having everyone—not just motorists—pay for such roads, parking, and gasoline), huge amounts of money could be made selling cars, homes and gasoline. The process eventually was feeding on itself in a growing, self-perpetuating way, because the highways, parking and subsidies were forcing and otherwise encouraging a growing number of Americans to buy more and more cars, use more and more gasoline, and buy sprawling homes that were further and further from the town center. Why? Because the subsidized highways and gasoline were powerfully promoting community dispersal, high speeds, isolation, and an insatiable demand for larger highways and parking lots. Each of these factors were toxic to a city, led to government and household financial difficulties, destroyed in-town quality of life (which added to the desire to live in sprawl locations), and made travel by transit, bicycle or walking increasingly difficult and unlikely (an added inducement to buy more cars).

The inevitable result of the Sprawl Lobby efforts has been that cities throughout America are dying from the “Gigantism” disease.

The “Gigantism” Disease

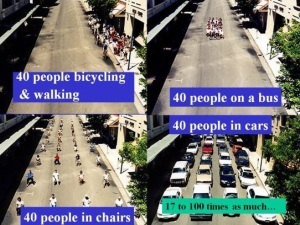

One of the most important problems we face is that cars consume enormous amounts of space. On average, a person in a parked car takes up about 17 times more space than a person in a chair. And when moving, a motorist can take up to 100 times as much space as a person in a chair. Cities are  severely diminished by this level of wasteful use of land by cars—particularly in town centers (where space is so dear), and especially in communities such as Boulder, where land is so expensive.

severely diminished by this level of wasteful use of land by cars—particularly in town centers (where space is so dear), and especially in communities such as Boulder, where land is so expensive.

Overemphasis on car travel breeds and spreads the gigantism “infection,” and promotes ruinously higher travel speeds. What happens when we combine the gigantism and high speeds with the “travel time budget” (humans tend to have a budget of about 1.1 hours of round-trip commuting travel each day)?

People demand larger highways and parking lots. Gigantic highways, overpasses, and asphalt seas of parking are necessary to accommodate the space-hogging, high-speed needs of the growing number of cars. This process dramatically increases the “habitat” for cars, and because such places are so utterly inhospitable to people, substantially shrinks the habitat for people.

Because it is so dangerous, unpleasant, and infeasible to travel on these monster highways by bicycle, walking, or transit (what economists call “The Barrier Effect”), an endlessly growing army of motorists and sprawl residents is thereby created, which, of course, is a financial bonanza for the Sprawl Lobby.

It is surprising and disappointing that Boulder has, on numerous occasions, shown symptoms of the gigantism disease (surprising because citizens and city staff are relatively well-informed on transportation issues). A leading concern in Boulder is the many intersections that have been expanded by installing double left turn lanes. Installing a single left turn lane historically resulted in a fair improvement in traffic flow, but when a second left turn lane is installed, intersections typically suffer from severely diminished returns. There is only a tiny increase in traffic accommodated (and often, this increase is short-lived) and this small benefit is offset by a huge required increase in walk time for crosswalks that are now very lengthy to cross on foot (which necessitates a very long “walk” phase for the crosswalk). Indeed, some traffic engineers or elected officials are so intolerant of the time-consuming long walk phase that many double-left turn intersections actually PROHIBIT pedestrian crossings by law.

These monster double left turn intersections destroy human scale and sense of place. They create a place-less, car-only intersection where walking and bicycling (and, indirectly, transit) trips are so difficult and unpleasant that more trips in the community are now by car, and less by walking, bicycling and transit. And those newly-induced car trips, despite the conventional wisdom, actually INCREASE greenhouse gas emissions (due to the induced increase in car trips).

Double left turn lanes (like big parking lots and five- or seven-lane highways) disperse housing, jobs, and shops in the community, as the intersection—at least briefly—is able to accommodate more regional car trips. Because the intersection has become so inhospitable, placeless and lacking in human scale, the double left turn repels any residences, shops, or offices from being located anywhere near the intersection, and thereby effectively prevents the intersection from ever evolving into a more walkable, compact, village-like setting.

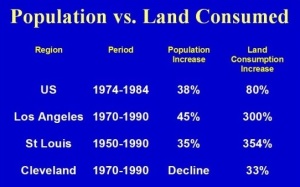

The following chart shows that, because of the enormous space consumption caused by higher-speed car travel, land consumption rate increases are far out-pacing growth in community populations. For  example, from 1950 to 1990, the St. Louis population grew by 35 percent. Yet land consumption in St. Louis grew by 354 percent during that same period.

example, from 1950 to 1990, the St. Louis population grew by 35 percent. Yet land consumption in St. Louis grew by 354 percent during that same period.

Given all of this, a centerpiece objective of the Boulder Transportation Master Plan (no more than 20 percent of road mileage is allowed to be congested) may not only be counterproductive in achieving many Boulder objectives, but may actually result in Boulder joining hands with the Sprawl Lobby.

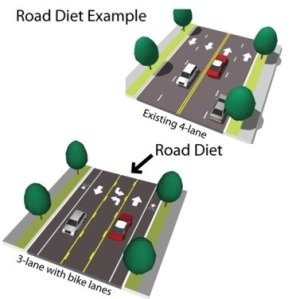

The congestion reduction objective has a number of unintended, undesirable consequences. The objective tells Boulder that the highly desirable tactic of “road diets” (where travel lanes are removed to create a safer, more human-scaled street that can now install bike lanes, on-street parking, and wider sidewalks) are actually undesirable because they can increase congestion. The objective provides justification for looking upon a wider road, a bigger intersection, or a bigger parking lot as desirable, despite the well-documented fact that such gigantic facilities promote sprawl, car emissions, financial difficulties, higher taxes, and lower quality of life, among other detriments.

The objective also tells us that smaller, more affordable infill housing is undesirable—again because such housing can increase congestion.

The Shocking Revolution

The growing awareness of the problems associated with easing car travel (via such things as a congestion reduction objective) is leading to a shocking revolution across the nation. Florida, for example, now realizes that if new development is only allowed if “adequate” road capacity is available for the new development (which is based on “concurrency” rules in Florida’s Growth Management law), the state is powerfully promoting sprawl. Why? Because the available road capacity tends to only be found in sprawl locations. In-town locations, where new development tends to be much more desirable, is strongly discouraged by this Florida concurrency rule because in-town locations tend to have no available road capacity (due to existing, more dense development in town).

As an aside, “concurrency” is a rule that says new development is not allowed if it will lower service level standards adopted by the community. For example, standards might state that there must be at least 10 acres of parkland provided for every 1,000 residents. While concurrency is clearly a good idea for such things as parks and water supply and schools, it is counterproductive for roads.

The shocking revolution in Florida, then, is that the state is now allowing local governments to create “exception areas” for road congestion. If the community can show that it is providing adequate bicycle, pedestrian and transit facilities, the state will grant the local government the ability to create road exceptions so that the road congestion avoidance strategy brought by Florida’s road concurrency rule does not significantly encourage new sprawl and discourage in-town, infill development.

Similarly, California is now acknowledging the unintended, undesirable effects of past efforts to ensure that roads are “free-flowing” for car traffic. “Free flowing” car traffic tends to be measured with “level of service” (LOS) measures. Road LOS is a measure of traffic delay. An intersection (or road) where a car must wait for, say, three cycles of a traffic signal to be able to proceed through the intersection might be given an LOS rating of “F.” An intersection where a car can proceed through an intersection without such delay is given an LOS rating of “A.”

California now realizes that too often, building wider highways or stopping new development as a way to maintain free-flowing car traffic (LOS “A”) is substantially counterproductive. The state now realizes that maintaining or requiring easy, free-flowing car traffic increases greenhouse gas emissions (shocking, since the opposite was formerly believed), increases the number of car trips, and decreases the number of walking, bicycling and transit trips. Free-flowing road “LOS” measures are therefore now being phased out in California.

The “congestion reduction” objective in Boulder’s transportation plan is, in effect, a “happy cars” objective that equates easy car travel with quality of life and sustainability. One important reason why this “happy cars” objective is counterproductive is that cars and people have dramatically different needs and desires—needs and desires that are significantly and frequently in conflict. For example, designing shopping for happy people means the creation of smaller, human-scaled settings where buildings rather than parking lots are placed next to the streetside sidewalk. Where streets are only two or three lanes wide and designed for slow-speed car travel. Where street trees hug the street.

Designing shopping for happy cars, by strong contrast, requires huge car-scaled dimensions. Giant asphalt parking lots are placed between the now giant retail store and the street, which invites easy car parking (but loss of human scale, sense of place, and ease of walking). Streets become what Chuck Marohn calls “stroads”: 5- or 7-lane monster roads intended for dangerous, inhospitable high-speeds. They are roads where streets belong, but their big size and high speeds make them more like roads. Street trees are frequently incompatible with happy cars, as engineers fear cars might crash into them.

Again, this comparison shows that by promoting “happy cars,” Boulder’s congestion reduction objective is undermining its important quality of life and city-building objectives.

Indeed, Enrique Penalosa, the former mayor of Bogota, Columbia, once stated that “a city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can’t be both.” Boulder’s congestion reduction objective is in conflict with this essential truth.

Fortunately, congestion regulates itself if we let it. Congestion will persuade some to drive at non-rush hour times, or take less congested routes, or travel by walking, bicycling, or transit. Congestion therefore does not inexorably lead to gridlock if we don’t widen a road or intersection, because some car trips (the “lower-value” trips) do not occur. Many of those discouraged trips are foregone because of the “time tax” imposed by the congestion.

But widening a road (or, in Boulder’s case, adding a second left-turn lane) short-circuits this self-regulation. A widened road or a double-left turn lane intersection induces new car trips because the road/intersection is now (briefly) less congested. The lower congestion encourages formerly discouraged car trips to now use the route during rush hour. Car trips that used different routes to avoid the congestion now converge back on the less congested route. And some get back in their cars after a period of walking, bicycling or using transit.

The process is very much like the infamous Soviet bread lines. The Soviets wanted to reduce the extremely long lines of people waiting for free bread. Their counterproductive “solution” was to make more free bread. But more free bread just induced more people to line up for bread. Likewise, the conventional American solution to traffic congestion is to make more free space for cars (widening the road or adding a second turn lane). The result is the same, as the bigger roads and intersections inevitably induce more car trips on those routes. The efficient and effective solution, as any first-year economics student will point out, is to NOT make more free bread or wider, free-to-use roads or second turn lanes. The solution is to price the bread and the car routes so that they are used more efficiently (and not wastefully by low-value bread consumers or car travelers). Or, to let a moderate level of congestion discourage low-value rush hour trips.

Given all of this, widening a road or adding a second left-turn lane to solve congestion is like loosening one’s belt to solve obesity. Similarly, despite conventional wisdom, car traffic does not behave like water flowing through a pipe (i.e., flowing easier if the pipe is expanded in size). Car traffic, instead, behaves like a gas. It expands to fill the available, increased volume provided.

Boulder’s Overriding Objectives

Boulder (and PLAN-Boulder County) has outlined key community objectives.

1. One is higher quality of life and more happiness. But counterproductively, happy cars lower quality of life due to clashing values and needs.

2. Another objective is for a more compact, walkable, vibrant city. Unfortunately, over-emphasizing cars means more sprawl.

3. An objective that is much talked about in the area is more affordability. By inducing more car dependence via easier car travel, the congestion reduction objective undermines the affordability objective by making Boulder less affordable (more on that later).

4. Given the growing concern for global warming, Boulder is placing more emphasis on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Easing traffic congestion, however, induces new car traffic, which increases car emissions.

5. Boulder and PLAN-Boulder County seek more travel (and lifestyle) choices. But the congestion reduction objective in Boulder’s plan is again undercutting other objectives because it leads to bigger car infrastructure (bigger roads and intersections), thereby reducing travel and lifestyle choices.

As shown above, then, Boulder’s congestion reduction objective undermines each of these five essential community objectives.

Oops.

Conventional methods of reducing congestion include wider roads, bigger parking lots, one-way streets, and huge intersections. These tactics are a “win-lose” proposition. While they can reduce congestion (briefly), they also cause a loss of human scale and charm; a loss of social gathering; sprawling dispersal; more car dependence and less bicycling, walking, transit; higher taxes; economic woes (for government, shops and households); a decline in public health; and more air pollution.

By striking contrast, other less commonly used but much more beneficial transportation tactics are “win-win” propositions. Some of these tactics include road diets, designing streets for slower speeds, and designing for travel and lifestyle choices. They can result in:

- More parking spaces

- More civic pride (induced by human scale)

- More social gathering

- A more compact and vibrant community

- Less car dependence and more bicycling, walking, and transit

- Lower taxes

- Economic health (for both government and households)

- Improvement in public health

- Less air pollution

If we can’t get rid of congestion, what CAN we do? We can create alternatives so that those who are unwilling to tolerate the congestion can find ways to avoid it. Congestion can be better avoided if we create more housing near jobs, shops, and culture. Doing this allows more people to have better, more feasible ways to travel without a car. We can also create more travel routes, so that the congested routes are not the only routes to our destinations. Some of us can be given more flexible work schedules to shift our work hours away from rush hour. And some of us can be given increased opportunities to telecommute (work from home).

How Can We Design Transportation to Achieve a Better Destiny?

An important way to start Boulder on a better destiny for the city is to revisit the “No more than 20 percent congested road miles” objective in the Boulder transportation master plan. Some possibilities: adopt a “level of service standard” not for cars, but for bicycle, walking and transit travel; “Level of service” standards for cars is becoming outdated because it is being increasingly seen as counterproductive, as described earlier. Other alternatives to the “congestion” objective is to have a target of controlling or reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) community-wide; or set a goal of minimizing trip generation by individual new developments in the city.

Another option is to keep the congestion objective, but create “exception” areas where the congestion rule does not apply. Those exception areas would be places where Boulder seeks to encourage new development.

Boulder needs to ensure that the community land development and transportation design tactics are appropriately calibrated within each “transect zone” of the community. (The “transect” principle identifies a transition from urban to rural, whereby the town center is more compact, formal, low-speed, and walkable; the suburbs are more dispersed, informal, higher-speed, and drivable; and the rural areas most remote from the town center are more intended for a farming and conservation lifestyle. Development regulations and transportation designs are calibrated so that the differing lifestyle and travel objectives of each zone are best achieved.) However, the difficulty with the transect principle in places like Boulder is that the demand for compact, walkable lifestyles and travel choices is much higher than the supply of such places in Boulder. There is, in other words, a large mismatch. By contrast, the supply of suburban, drivable areas is quite high. To correct this imbalance, Boulder should strive to create a larger supply of compact, walkable places similar to Pearl Street Mall, the Boulder town center, and even the CU campus. Opportunities now being discussed are the creation of new, compact villages and town centers at places such as street intersections outside of the Boulder town center.

As an aside, the community transect concept informs us that in the town center, “more is better.” That is, the lifestyle being sought in the community center is one where more shops, more offices, and more housing enhances the lifestyle, as this more proximate, mixed, compact layout of land uses provides the thriving, sociable, convenient, vibrant, 24-hour ambience that many seeking the walkable lifestyle want more of.

By contrast, in the more drivable suburbs, “more is less.” That is, the drivable lifestyle is enhanced in quality when there is less density, less development, more dispersal, and more isolation of houses from shops and offices. The ambience generally desired is more quiet and private.

While town center housing is increasingly expensive compared to the suburbs—particularly in cities such as Boulder—such in-town housing provides significant cost savings for transportation. Because such a housing location provides so many travel choices beyond car travel, many households find they can own two cars instead of three or one car instead of two. And each car that a household can “shed” due to the richness of travel choices provides more household income that can be directed to housing expenses such as a mortgage or rent. Today, the average car costs about $9,000 per year to own and operate. In places that are compact and walkable, that $9,000 (or $18,000) per year can be devoted to housing, thereby improving affordability.

In addition to providing for the full range of housing and travel choices, Boulder can better achieve its objectives through road diets, where travel lanes are removed and more space is provided for such things as bike lanes or sidewalks or transit. Road diets are increasingly used throughout the nation—particularly converting roads from four lanes to three. Up to about 25,000 vehicle trips per day on the road, a road that is “dieted” to, say, three lanes carries about as much traffic as a four-lane road. This is mostly due to the fact that the inside lanes of a four-laner frequently must act as  turn lanes for cars waiting to make a left turn. Four-lane roads are less desirable than three-lane streets because they induce more car trips and reduce bicycle, walking and transit trips. Compared to three-lane streets, four-lane roads result in more speeding traffic. As a result, four-laners create a higher crash rate than three-lane streets. Finally, because the three-lane street is more human-scaled, pleasant, lower-speed, and thereby place-making, a three-lane street is better than a four-lane street for shops. The three-lane street becomes a place to drive TO, rather than drive THROUGH (as is the case with a four-lane street).

turn lanes for cars waiting to make a left turn. Four-lane roads are less desirable than three-lane streets because they induce more car trips and reduce bicycle, walking and transit trips. Compared to three-lane streets, four-lane roads result in more speeding traffic. As a result, four-laners create a higher crash rate than three-lane streets. Finally, because the three-lane street is more human-scaled, pleasant, lower-speed, and thereby place-making, a three-lane street is better than a four-lane street for shops. The three-lane street becomes a place to drive TO, rather than drive THROUGH (as is the case with a four-lane street).

If Boulder seeks to be transformative with transportation—that is, if the city seeks to significantly shift car trips to walking, bicycling and transit trips (rather than the relatively modest shifts the city has achieved in the past)—it must recognize that it is NOT about providing more bike paths, sidewalks, or transit service. It is about taking away road and parking space from cars, and taking away subsidies for car travel.

Another transportation tactic Boulder should pursue to achieve a better destiny is to unbundle the price of parking from the price of housing. People who own less (or no) cars should have the choice of opting for more affordable housing—housing that does not include the very expensive cost of provided parking. Currently, little or no housing in Boulder provides the buyer or renter the option of having lower cost housing payments by choosing not to pay for parking. Particularly in a place like Boulder, where land values are so high, even housing intended to be relatively affordable is more costly than it needs to be because the land needed for parking adds a large cost to the housing price. Indeed, by requiring the home buyer or renter to pay more for parking, bundled parking price creates a financial incentive for owning and using more cars than would have otherwise been the case.

Boulder should also strive to provide parking more efficiently by pricing more parking. Too much parking in Boulder is both abundant and free. Less parking would be needed in the city (which would make the city more affordable, by the way) if it were efficiently priced. Donald Shoup recommends, for example, that parking meters be priced to ensure that in general, 2 or 3 parking spaces will be vacant on each block.

Efficient parking methods that could be used more often in Boulder include allowing shops and offices and churches to share their parking. This opportunity is particularly available when different land uses (say churches and shops) don’t share the same hours of operation. Again, sharing more parking reduces the amount of parking needed in the city, which makes the city more compact, walkable, enjoyable and active.

Like shared parking, leased parking allows for a reduction in parking needed. If Boulder, for example, owns a parking garage, some of the spaces can be leased to nearby offices, shops, or housing so that those particular land uses do not need to create their own parking.

Finally, a relatively easy and quick way for Boulder to beneficially reform and make more efficient its parking is to revise its parking regulations so that “minimum parking” is converted to “MAXIMUM parking.” Minimum parking rules, required throughout Boulder, are the conventional and increasingly outmoded way to regulate parking. They tell the developer that at least “X” amount of parking spaces must be provided for every “Y” square feet of building. This rule almost always requires the developer to provide excessive, very expensive parking, in large part because it is based on “worst case scenario” parking “needs.” That is, sufficient parking must be provided so that there will be enough on the busiest single day of the year (often the weekend after Thanksgiving). Such a provision means that for the other 364 days of the year, a large number of parking spaces sit empty, a very costly proposition.

In contrast, maximum parking rules tell the developer that there is an upper limit to the number of spaces that can be provided. This works much better for the community and the business because the business is better able to choose how much parking it needs and can finance. Since financial institutions that provide financing for new developments typically require the developer to provide the conventional (read: excessive) amounts of parking as a condition for obtaining a development loan, the big danger for communities in nearly all cases is that TOO MUCH parking will be provided rather than too little. The result of setting “maximum” instead of “minimum” parking rules is that excessive, worst case scenario parking developments become much more rare.

The reform of parking is easy: simply convert the existing minimum parking specifications to maximum parking standards (“at least 3 spaces per 1,000 square feet” becomes “no more than 3 spaces per 1,000 square feet). An incremental approach to this conversion is to apply maximum parking rules in those places that are already rich in travel choices, such as the Boulder town center.

Again, what will Boulder’s destiny be? As the preceding discussion sought to demonstrate, much of that destiny will be shaped by transportation decisions.

Will destiny be shaped by striving for happy people and happy places for people? Or will it be shaped by opting for the conventional, downwardly-spiraling effort of seeking easy car travel (and thereby unpleasant places where only a car can be happy – such as huge highways or parking lots)?

Will Boulder, in other words, retain or otherwise promote place-less conventional shopping centers full of deadening parking, car-only travel, lack of human interaction, and isolation? Or will the city move away from car-happy objectives such as the congestion reduction policy, and instead move toward a people-friendly future rich in sociability, pride in community, travel choices, sustainability, place-making and human scale?

An example of these contrasting destinies is Pearl Street. West Pearl features the charm and human scale we built historically. West Pearl Street exemplifies a lovable, walkable, calm, safe and inviting ambience where car speeds are slower, the street is more narrow, and the shops—by being pulled up to the streetside sidewalk—help form a comfortable sense of enclosure that activates the street and feels comfortable to walk. The shops tend to be smaller—more neighborhood-scaled.

East Pearl Street near 28th Street is starkly different. There, the street is a “stroad,” because it is an overly wide road that should be a more narrow, lower-speed street. Shops are pulled back long distances from the street. The street here is fronted not by interesting shop fronts but enormous seas of asphalt parking. The layout is car-scaled. The setting is hostile, unpleasant, unsafe, stressful and uninviting. The shops tend to be “Big Box” retail, and serve a regional “consumershed.” There is “no there there.”

East Pearl Street was built more recently by professional planners and engineers who have advanced degrees that far exceed the professionalism and education of those who designed the more lovable West Pearl Street. Where has the charm gone? Why have our streets become less pleasant in more recent years (by better trained and better educated designers, I might add)? Is it perhaps related to our more expensive and sophisticated efforts to ease car traffic and reduce congestion?

There is an inverse relationship between congestion and such measures as vehicle miles traveled and gas consumption. At the community level—despite the conventional wisdom—as congestion increases, vehicle miles traveled, gas consumption, air emissions DECREASE. And as conventional efforts to reduce congestion intensify, quality of life and sustainability also decrease.

Again, is Boulder aligning itself with the Sprawl Lobby by maintaining an objective of easing traffic flow – by striving to reduce congestion?

On Controlling Size

David Mohney reminds us that the first task of the urban designer is to control size. This not only pertains to the essential need to keep streets, building setbacks, and community dispersal modest in size. It also pertains to the highly important need to insist on controlling the size of service and delivery trucks. Over-sized trucks in Boulder lead the city down a ruinous path, as street and intersection dimensions are typically driven by the “design vehicle.” When trucks are relatively large, excessive truck size becomes the “design vehicle” which ends up driving the dimensions of city streets. A healthy city should be designed for human scale and safety, not for the needs of huge trucks. Indeed, because motor vehicles consume so much space, a sign of a healthy, well-designed community is that drivers of vehicles should feel inconvenienced. If driving vehicles feels comfortable, it is a signal that we have over-designed streets and allocated such excessive spaces that we have lost human scale and safety.

A proposal for human-scaled streets: in Boulder’s town center, no street should be larger than three lanes in size. Outside the town center, no street should be larger than five lanes in size. Anything more exceeds the human scaling needed for a pleasant, safe, sustainable community.

It is time to return to the timeless tradition of designing to make people happy, not cars. Boulder needs to start by revisiting its congestion reduction objective, putting a number of its roads on a “road diet,” and taking steps to make the provision of parking more efficient and conducive to a healthy city.

________________________________________

More about the author

Mr. Nozzi was a senior planner for Gainesville FL for 20 years, and wrote that city’s long-range transportation plan. He also administered Boulder’s growth rate control law in the mid-90s. He is currently a member of the Boulder Transportation Advisory Board.

Studies Demonstrating Induced Traffic and Car Emission Increases

Below is a sampling of references to studies describing how new car trips are induced by easier car travel, and how car emissions increase as a result.

http://www.sierraclub.org/sprawl/articles/hwyemis.asp

http://www.vtpi.org/gentraf.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induced_demand

TØI (2009), Does Road Improvement Decrease Greenhouse Gas Emissions?, Institute of Transport Economics (TØI), Norwegian Centre for Transport Research (www.toi.no); summary at www.toi.no/getfile.php/Publikasjoner/T%D8I%20rapporter/2009/1027-2009/Sum-1027-2009.pdf

Robert Noland and Mohammed A. Quddus (2006), “Flow Improvements and Vehicle Emissions:

Effects of Trip Generation and Emission Control Technology,” Transportation Research D, Vol. 11 (www.elsevier.com/locate/trd), pp. 1-14; also see

www.cts.cv.ic.ac.uk/documents/publications/iccts00249.pdf

Clark Williams-Derry (2007), Increases In Greenhouse-Gas Emissions From Highway-Widening Projects, Sightline Institute (www.sightline.org); at

www.sightline.org/research/energy/res_pubs/analysis-ghg-roads

TRB (1995), Expanding Metropolitan Highways: Implications for Air Quality and Energy Use,

Committee for Study of Impacts of Highway Capacity Improvements on Air Quality and Energy

Consumption, Transportation Research Board, Special Report #345 (www.trb.org)

D. Shefer & P. Rietvald (1997), “Congestion and Safety on Highways: Towards an Analytical Model,” Urban Studies, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 679-692.

Alison Cassady, Tony Dutzik and Emily Figdor (2004). More Highways, More Pollution: Road Building and Air Pollution in America’s Cities, U.S. PIRG Education Fund (www.uspirg.org).

http://www.opr.ca.gov/docs/PreliminaryEvaluationTransportationMetrics.pdf